Touchpads, or trackpads, have been around since the 1980s. Today, you can often find them in laptops and notebook computers as pointing devices. With no moving parts, a trackpad are easy to integrate into the body of a portable computer. they’re much smaller than the traditional mouse. Until the advent of multitouch and gestures over the past two decades, though, they were generally poor substitutes for an actual mouse. These days, trackpads have enough features that some users prefer them even on their desktop computers. If you’re that type of person and don’t want to shell out a big pile of money for an Apple, Logitech, or other off-the-shelf trackpad you can always build your own.

mouse193 Articles

Turn A Mouse Into An Analogue Tuning Knob

The software defined radio has opened up unimaginable uses of the radio spectrum for radio enthusiasts, but it’s fair to say that there’s one useful feature of an old-fashioned radio they lack when used via a computer. We’re talking of course about the tuning knob, because it represents possibly the most intuitive way to move across the bands. Never fear though, because [mircemk] has a solution. He’s converted a mouse into a tuning dial.

The scroll wheel on a mouse is nothing more than a rotary encoder, and can easily be used as a sort of tuning knob. Replacing it with a better encoder gives it a much better feel, so that’s what he’s done. An enclosure has the guts of a mouse, with the front-mounted encoder wired into where the scroll wheel would have been. The result, for a relatively small amount of work, is a tuning knob, and a peripheral we’re guessing could also have a lot of uses beyond software defined radio.

It’s not the first knob we’ve seen, for that you might want to start with the wonderfully named Tiny Knob, but it’s quite possibly one of the simplest to build. We like it.

Tiny Trackpad Fits On Ergonomic Keyboard

Cats are notorious for interrupting workflow. Whether it’s in the kitchen, the garden, or the computer, any feline companion around has a way of getting into mischief in an oftentimes disruptive way. [Robin] has two cats, and while they like to sit on his desk, they have a tendency to interrupt his mouse movements while he’s using his Apple trackpad. Rather than solve the impossible problem of preventing cats from accessing areas they shouldn’t, he set about building a customized tiny trackpad that integrates with his keyboard and minimizes the chance of cat interaction.

The keyboard [Robin] uses is a split ergonomic keyboard. While some keyboards like this might use a standard USB connection to join the two halves, the ZSA Voyager uses I2C instead and even breaks the I2C bus out with a pogo pin-compatible connector. [Robin] originally designed a 3D-printed integrated prototype based on a Cirque trackpad that would clip onto the right side of the keyboard and connect at this point using pogo pins, but after realizing that the pogo pin design would be too difficult for other DIYers to recreate eventually settled on tapping into the I2C bus on the keyboard’s connecting cable. This particular keyboard uses a TRRS connector to join the two halves, so getting access to I2C at this point was as simple as adding a splitter and plugging in the trackpad.

With this prototype finished, [Robin] has a small trackpad that seamlessly attaches to his ergonomic keyboard, communicates over a standard protocol, and avoids any unwanted cat-mouse action. There’s also a build guide if you have the same keyboard and want to try out this build. He does note that using a trackpad this small involves a bit of a learning curve and a larger-than-average amount of configuration, but after he got over those two speed bumps he hasn’t had any problems. If trackpads aren’t your style, though, with some effort you can put a TrackPoint style mouse in your custom mechanical keyboard instead.

Uncovering Secrets Of Logitech M185’s Dongle

[endes0] has been hacking with USB HID recently, and a Logitech M185 mouse’s USB receiver has fallen into their hands. Unlike many Logitech mice, this one doesn’t include a Unifying receiver, though it’s capable of pairing to one. Instead, it comes with a pre-paired CU0019 receiver that, it turns out, is based on a fairly obscure TC32 chipset by Telink, the kind we’ve seen in cheap smart wristbands. If you’re dealing with a similarly obscure MCU, how do you even proceed?

In this case, GitHub had a good few tools developed by other hackers earlier — a Ghidra integration, and a tool for working with the MCU using a USB-UART and a single resistor. Unfortunately, dumping memory through the MCU’s interface was unreliable and frustrating. So it was time to celebrate when fuzzing the HID endpoints uncovered a memory dump exploit, with the memory dumper code helpfully shared in the blog post.

In this case, GitHub had a good few tools developed by other hackers earlier — a Ghidra integration, and a tool for working with the MCU using a USB-UART and a single resistor. Unfortunately, dumping memory through the MCU’s interface was unreliable and frustrating. So it was time to celebrate when fuzzing the HID endpoints uncovered a memory dump exploit, with the memory dumper code helpfully shared in the blog post.

From a memory dump, the exploration truly began — [endes0] uncovers a fair bit of dongle’s inner workings, including a guess on which project it was based on, and even a command putting the dongle into a debug mode where a TC32-compatible debugger puts this dongle fully under your control.

Yet another hands-on course on Ghidra, and a wonderful primer on mouse dongle hacking – after all, if you treat your mouse’s dongle as a development platform, you can easily do things like controlling a small quadcopter, or pair the dongle with a SNES gamepad, or build a nifty wearable.

We thank [adistuder] for sharing this with us!

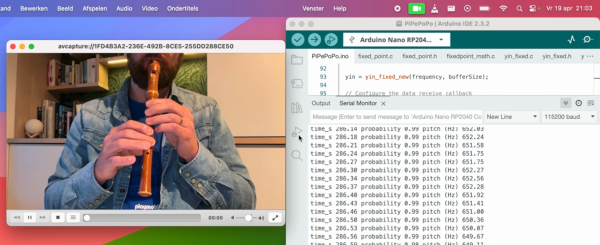

Flute Now Included On List Of Human Interface Devices

For decades now, we’ve been able to quickly and reliably interface musical instruments to computers. These tools have generally made making and recording music much easier, but they’ve also opened up a number of other out-of-the-box ideas we might not otherwise see or even think about. For example, [Joren] recently built a human interface device that lets him control a computer’s cursor using a flute instead of the traditional mouse.

Rather than using a MIDI interface, [Joren] is using an RP2040 chip to listen to the flute, process the audio, and interpret that audio before finally sending relevant commands to control the computer’s mouse pointer. The chip is capable of acting as a mouse on its own, but it did have a problem performing floating point calculations to the audio. This was solved by converting these calculations into much faster fixed point calculations instead. With a processing improvement of around five orders of magnitude, this change allows the small microcontroller to perform all of the audio processing.

[Joren] also built a Chrome browser extension that lets a flute player move a virtual cursor of sorts (not the computer’s actual cursor) from within the browser, allowing those without physical hardware to try out their flute-to-mouse skills. If you prefer your human interface device to be larger, louder, and more trombone-shaped we also have a trombone-based HID for those who play the game Trombone Champ.

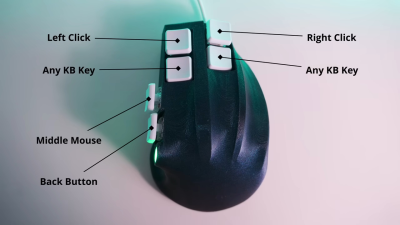

An Open-Source Gaming Mouse

It’s a shame, that peripherals sold as of higher performance for gaming so often deliver little but aggressive styling. [Wareya] became frustrated with the fragile switches on his choice of gaming mouse, so decided to design his own. In the video that he’s placed below the break, he takes us through all the many choices and pitfalls inherent to these devices

After quite a few iterations he arrived upon a design featuring an RP2040 and an optical sensor easily found in relatively inexpensive mice. The whole design is open source and can be found in a GitHub repository, but for us perhaps the most interesting part of the explanation lies in the use of a three-contact switch, and how the third contact is used to aid in debouncing. In an application in which latency is of paramount importance this is a key design feature of a gaming mouse.

Perhaps it’s a mark of how good computer mice are in general that we see so relatively few projects building them from scratch rather than modifying exiting ones, but despite that a few have made it to these pages. Continue reading “An Open-Source Gaming Mouse”

Custom Mouse-Making: Clay Is The Way

For something that many of us handle all day long, it sure would be nice if mice came in more sizes and shapes, wouldn’t it? Until that day, we’ll just have to find something passable or else design and build a custom-shaped mouse from scratch like [Ben Makes Everything] did.

First, [Ben] played around with some modelling clay until he had a shape he was happy with, then took a bunch of pictures of it mounted on a piece of wood for easy manipulation and used photogrammetry to scan it in for printing after cleaning it up in Blender. About six versions later, he had the final one and was ready to move on to electronics.

First, [Ben] played around with some modelling clay until he had a shape he was happy with, then took a bunch of pictures of it mounted on a piece of wood for easy manipulation and used photogrammetry to scan it in for printing after cleaning it up in Blender. About six versions later, he had the final one and was ready to move on to electronics.

That’s right, this isn’t just mouse guts in an ergonomic package. Inside is Arduino Pro Micro and a PMW 3389 optical sensor on a breakout board. [Ben] was going to use flexible 3D printed panels as mouse buttons, but then had an epiphany — why not use keyboard switches and keycaps instead? He also figured he could have two buttons per finger if he wanted, so he went with Kailh reds for the fingers and and whites in the thumb.

Speaking of the thumb, there was no room for a mouse wheel in between those comparatively huge switches, so he moved it to the the side to be thumb-operated. [Ben] got everything working, and after all this, decided to make it wireless. So he switched to an Adafruit Feather S3 and designed his first PCB for both versions. Ultimately, he found that the wireless version is kind of unreliable, so he is sticking with the wired one for now.