When a new technology first arrives in people’s hands, it often takes a bit of time before the full capabilities of that technology are realized. In much the same way that many early Internet users simply used it to replace snail mail, or early smartphones were used as more convenient methods for messaging and calling than their flip-phone cousins, autonomous drones also took a little bit of time before their capabilities became fully realized. While some initially used them as a drop-in replacement for things like aerial photography, a group of mountain rescue volunteers in the United Kingdom realized that they could be put to work in more efficient ways suited to their unique abilities and have been behind a bit of a revolution in the search-and-rescue community.

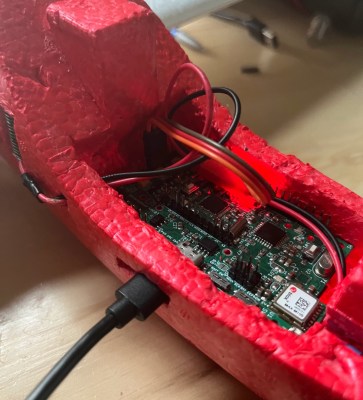

The first search-and-rescue groups using drones to help in their efforts generally used them to search in the same way a helicopter would have been used in the past, only with less expense. But the effort involved is still the same; a human still needed to do the searching themselves. The group in the UK devised an improved system to take the human effort out of the equation by sending a drone to fly autonomously over piece of mountainous terrain and take images of the ground in such a way that any one thing would be present in many individual images. From there, the drone would fly back to its base station where an operator could download the images and run them through a computer program which would analyse the images and look for outliers in the colors of the individual pixels. Generally, humans tend to stand out against their backgrounds in ways that computers are good at spotting while humans themselves might not notice at all, and in the group’s first efforts to locate a missing person they were able to locate them almost immediately using this technology.

Although the system is built on a mapping system somewhat unique to the UK, the group has not attempted to commercialize the system. MR Maps, the software underpinning this new feature, has been free to use for anyone who wants to use it. And for those just starting out in this field, it’s also worth pointing out that location services offered by modern technologies in rugged terrain like this can often be misleading, and won’t be as straightforward of a solution to the problem as one might think.